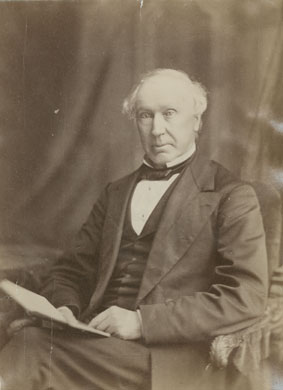

Merchants: Sir Edward Kenny

In the nineteenth-century a number of Irish Catholics became prominent members of Halifax’s mercantile elite. Michael Tobin, William Stairs, Patrick Power and Isaac Morrow made considerable fortunes in the port city. Buried near the chapel of “Our Lady of Sorrows” is one of the most prominent of these businessmen, Sir Edward Kenny. Born in July 1800 at Kilmoyly in the Barony of Clanmaurice, County Kerry, Kenny entered the world not two years after the ill-fated 1798 rebellion and five months before the Act of Union brought Ireland into a United Kingdom with England and Scotland.

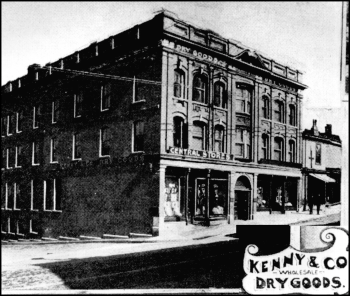

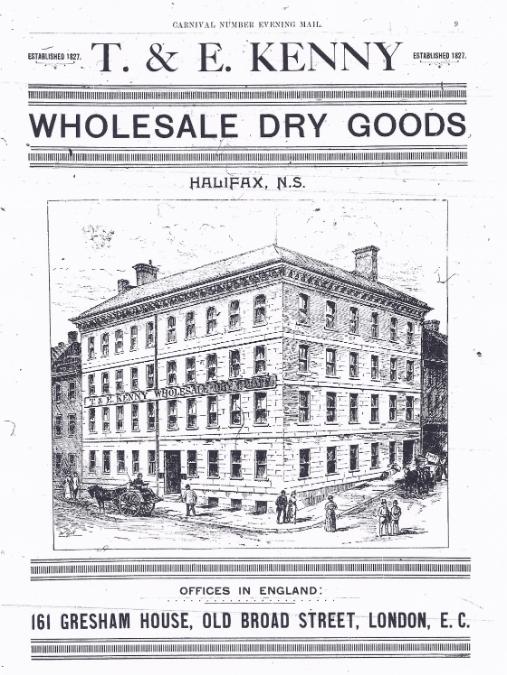

As young men, Kenny and his brother Thomas moved to the port city of Cork and found employment as clerks with James Lyons, a merchant who had business connections with Halifax. Lyons regularly brought dry goods and other provisions (beaver hats, hosiery, salmon, brandy and glassware) to Halifax, and ingratiated himself with the burgeoning Irish community. In fact, Lyons was elected president of the Charitable Irish Society in 1823. Both Kenny brothers migrated to Nova Scotia in the employ of Lyons in 1824, and by 1827 Edward became a partner in the business. In 1828, the Novascotian reported the dissolution of the partnership and the establishment of T& E Kenny in the store “lately occupied by T. Kenny, No. 24 Hollis Street, opposite the province building.” Involved in the trade of linen, woolen, and fancy, they soon moved their location to offices on Barrington Street and erected “an imposing granite office-warehouse complex.”

?Although Kenny’s crossing of the Atlantic was comfortable, there was fierce debate in Nova Scotia concerning the regulation of passenger ships from Ireland. Most believed that despite the escalating expenditure, it was “unchristian” to transport women and children in squalid conditions aboard dilapidated ships. Others, such as the colony’s former attorney general, Richard John Uniacke, an Irishmen himself, believed that the alternative for many migrants was to reach America aboard a Newfoundland fishing vessel. Consequently, argued Uniacke, the acts actually made the situation worse. Kenny and his brother took advantage of the passenger acts to promote ships “of the first class” for Irish migrants. In the autumn of 1828, the Novascotian carried an advertisement from T & E Kenny advising persons with relatives in Cork, Limerick and Kerry that a large vessel was sailing from Tralee for Saint John New Brunswick and Halifax the following spring. Applications for the “desired opportunity” would be taken at the brother’s shop.

On 16 October, 1832, at the unusually late age of 32, the “fine-looking” Kenny married Ann Forrestall, a member of a prominent Irish-Antigonish family.The marriage provided Kenny with a number of invaluable contacts. His wife’s brother, Richard John Forrestall was the first Roman Catholic elected to the provincial assembly from the County of Sydney in 1837 and her half-brother, W.A. Henry, was a prominent lawyer and future “father of confederation”.

As leading merchants the Kennys held prominent positions in St. Mary’s Parish (previously called St. Peter’s). Thomas Kenny was first listed as an “elector” in 1823 and as a “warden” in 1828. Edward was persuaded to follow his brother into the parish leadership in 1834 as an “elector”, and as a “warden” in 1836. As Terrence Murphy illustrates, the trustees were drawn from a “small but rising Catholic bourgeoisie”, eager to be “accepted into ‘responsible’ society.” Not satisfied with the status quo, Kenny and other leading Halifax Catholics successfully pressured Rome to divide the Diocese of Nova Scotia into two (one part for the Irish and the other for the Scots) and to provide the community with an Irish prelate.

By advocating for an Irish diocese, Kenny became a conspicuous leader in Irish-Halifax. In 1842, he was elected president of the Charitable Irish Society, which placed him at the very fore of the community. He attended and spoke at the community’s important social and religious events. In politics Kenny was rumored to be a moderate, and as a Catholic he was a supporter of the reform movement in the colony. In 1841 he was appointed to the colony’s Legislative Council by Governor Lord Falkland. Kenny’s inclusion on the Legislative Council was rooted in Joseph Howe’s desire to put committed reformers in positions of power, and his friendship with the newspaperman was valuable. Kenny was a adamant reformer and certainly, as the Morning Chronicle argued years later, “did the country a good turn” when the liberals were struggling for reform. In 1842, when the Mayor of Halifax, Stephen Binney, forfeited his office due to an elongated stay in England, Kenny was appointed to complete his term.

Despite his political advocacy, Edward Kenny’s primary concern was business. In 1856 trade was flourishing in Halifax and there was plenty of surplus capital. Kenny and a number of prominent merchants, which included William Stairs and John W. Ritchie, formed the Union Bank. It was, as James Frost argues, founded “out of a growing frustration with the existing Halifax banks,” which were “too restrictive in terms of providing access to capital and were therefore holding back the city’s progress.” The bank was considered to be quite conservative, which allowed “freedom from large losses.” Widely considered the most successful of the Halifax banks, it was the first financial institution to offer a regular dividend of ten per cent. Within a few years the Union Bank had many influential and wealthy customers and some twenty branches across the colony.

Seven years after the founding of the Union Bank, Kenny and his son were involved in another financial endeavor when they helped establish the Merchants Bank of Halifax. The bank was opened in response to the growing prosperity brought on by the American Civil War. Kenny’s son, Thomas E., took a more prominent role in the operation of the Merchants Bank and became president in 1870. The institution soon had branches throughout the province.

By the 1860s, Kenny was one of the wealthiest men in Nova Scotia, and one of the most prominent Irishmen in British North America. When the author, Irish nationalist and Member of Parliament for Cork city, James Maguire, arrived for a visit to Halifax, both Kenny, John Tobin, Fr. Hannan and Patrick Power organized a public dinner on his behalf. Kenny had a love of horses and his “riding and driving”, argued one historian, “no doubt contributed to the good health which he enjoyed through an unusually long life.” He was also known for his wit. “There is a story that Laurence O'Connor Doyle, Edward Kenny and James Uniacke were at dinner. Kenny took a drink of wine and got a bit of cork in his windpipe, which brought on a terrible coughing fit. When he stopped, Uniacke observed that ‘that was the wrong road for Cork.’ Quick as the thought, Doyle exclaimed, ‘It may be the wrong road for Cork, but it went nigh to Kilkenny!’”

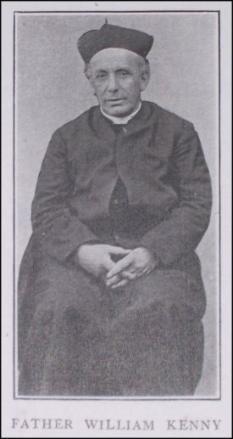

In 1862, Kenny, his brother, and his two sons helped to found the prestigious Halifax Club. His children were also beginning prominent careers of their own. In 1859, Kenny’s daughter, Joanna, married the Quebec-born lawyer Malachy Bowes Daly (she brought with her a $40,000 dowry). Daly's father, Sir Dominick Daly, had just ended his term as Governor of Prince Edward Island and was soon to depart for a similar position in South Australia. Later (1875) Mary Anne would wed Admiral Sir Charles George Fane. While three of the boys followed their father into the family business, three others (George, William and Joseph) opted for careers in the Society of Jesus. One of those priests, George, was a prominent professor at Fordham University and for a short time was Rector of St. Dunstan’s College in Charlottetown. A daughter entered the society of the Sacred Heart and spent her career in St. Louis Missouri.

After Canadian confederation in 1867, Sir John A. MacDonald requested that Kenny represent Nova Scotia in his cabinet. Kenny happened to be Nova Scotian and Catholic, two features which MacDonald needed to maintain the tricky balance in his government. The Archbishop of Halifax, Thomas Louis Connolly, wrote that he had not interfered in Kenny’s appointment to the senate; rather it originated “on public grounds in Ottawa.” He was, however, responsible “for having forced him to have accepted it” and was “proud of that act.”

In 1870, Kenny resigned his seat in cabinet to make room for Charles Tupper and was given the post of administrator of the government of Nova Scotia. “We have no fault with the appointment of Mr. Kenny,” argued the Liberal Morning Chronicle, and as no one but a confederate could occupy the office, the editors were “truly glad that a gentleman who has done so little to make himself obnoxious to the dominant party in this province has received the appointment.” Shortly after Kenny left Cabinet he was knighted, compensation it was believed for his political sacrifice to the dominion government.

By the late 1860s, Archbishop Connolly described Kenny as “the third or perhaps the second richest man in Nova Scotia.” His brother, Thomas, died a bachelor in 1868 and left him a considerable fortune. In retirement, Kenny was kept busy with the exploits of his extended family. His son-in-law, Malachy Bowes Daly was successful in capturing a parliamentary seat for Halifax in 1878 (and eventually became Lieutenant Governor of the province). He stayed involved with the Charitable Irish Society, and during funerals of deceased members, he and his colleagues humbly escorted the corpse to the burial site at Holy Cross Cemetery. His name was also used in defense of Catholicism. When the Jesuits were attacked in Ottawa, one apologist replied that Fr George Kenny was the son of Sir Edward who was the very “quintessence of loyalty.” Everybody in Halifax knows who the Kennys are, he continued “and you would be laughed at if you suspected them of being disloyal.”

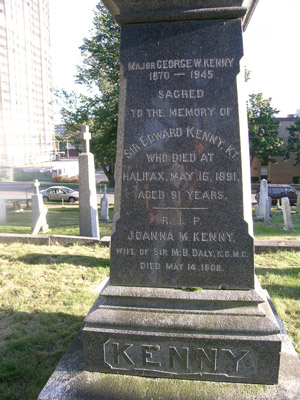

Kenny lived a charmed retirement. He was “highly respected” in social circles and was a “noticeable figure” on the streets of the city.He regularly attended Mass at St. Mary’s and was “strict in his religious duties.” Edward Kenny died at his residence (197 Pleasant Street) on 16 May 1891. Two days later, the Charitable Irish Society met at Masonic Hall and promptly adjourned out of respect “to the memory” of the deceased. He was, as the Morning Chronicle proclaimed, “for 63 years a member of the society.” Although most of Kenny’s contemporaries were gone by the time of his death, his passing fostered a period of reflection “on old Halifax.” The newspapers mused that his death “ended the chain of businessmen in Halifax between the years 1830 and 1880.” He was also a relic of an explosive time in Nova Scotia politics, and many of the newspapers which proclaimed his virtues at the time of his death, “did not hesitate to lash him with the type on account of his vote or his speech.”

His estate was considerable. He left his heirs more than $200,000, “which included $71,000 in real and personal property, $87,000 in bank stock, $9,000 in miscellaneous other corporate securities, and $33,000 in mortgages.” The Kenny named remained prominent in the years after his death. As wife of the Lieutenant Governor, his daughter entertained the elite of Halifax society. His daughter-in-law, Mrs Joseph Kenny, was prominent in the community’s cultural scene and was the host of some of Halifax’s most elegant dances. By 1901, however, the Merchants Bank had become the Royal Bank of Canada and by 1907 its head office was moved to Montreal. It was not long before Edward Kenny, the prominent merchant, politician and senator disappeared from Nova Scotia’s historiography altogether.

Further Reading:

Dan Bunbury, “Safe Haven for the Poor? Depositors and the Government Savings Bank in Halifax, 1832-1867.” Acadiensis, 24, 2 (1995): 24-48.?

Dan G.F. Butler, “The Early Organization and Influence of Halifax Merchants,” Collections of the N.S. Historical Society, 25 (1942):1-16. (View Butler Article)

James Frost, Merchant Princes: Halifax’s First Family of Finance, Ships and Steel (Toronto: Lorimer, 2003).

James Frost, “The Union Bank of Halifax, 1856-1910.” Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, 15 (2012): 82-102. (View Frost Article)

Julian Gwyn, “Golden Age or Bronze Moment? Wealth and Poverty in Nova Scotia: the 1850s and 1860s.” In Donald Akenson (ed.) Canadian Papers in Rural History, Volume 8 (Gananoque: Langdale Press, 1992): 195-230. (View Gwyn Article)

Halifax and Its Business (Halifax: G.A. White, 1876).

Terrence Murphy, “Trusteeism in Atlantic Canada: The Struggle for Leadership among the Irish Catholics of Halifax, St. John’s, and Saint John, 1780-1850”, in Terrence Murphy and Gerald Stortz, Creed and Culture: The Place of English-Speaking Catholics in Canadian Society, 1750-1930 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993):126-151. (View Murphy Article)

C. Alexander Pincombe, “Binney, Stephen” DCB, Volume X (1972).

Kenneth G. Pryke, Nova Scotia and Confederation 1867-1874 (Toronto: University of T Press, 1979).

Terrence M. Punch, Some Sons of Erin in Nova Scotia (Halifax: Petheric Press 1980).

D.A. Sutherland, “Kenny, Sir Edward,” DCB, Volume XII (1990).

D.A. Sutherland, “Halifax Merchants and the Pursuit of Development, 1783-1850.” Canadian Historical Review, 59, 1 (1978): 1-17. (View Sutherland Article)