The Irish in Politics

The protracted struggle by the Irish Catholic elite for their own diocese in 1844, as well as the local organisation in support for the repeal of the Act of Union between Ireland and Britain, fostered a new political awareness among the Irish Catholics of Halifax in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1822 the first “papist”, Laurence Kavanagh (1764-1830), a wealthy merchant from Cape Breton, entered the colonial legislature when the required oath against transubstantiation was abolished. Although a few of the wealthy Irish Catholics that had fought for an Irish Roman Catholic diocese, such as Michael Tobin Sr., remained in the Tory camp, content with the status quo, most of the Halifax-Irish elite became prominant in the movement for political reform in Nova Scotia.

[Gravemarker of repealer Thomas Ring (1806-1862) and his wife Catherine (1794-1864)]

Those Irish Catholics that supported Joseph Howe and the reform movement did so because they believed that responsible government was the best way of moving the Irish Catholic community forward. The community was woefully underrepresented in government. In fact, when the city of Halifax was incorporated in 1841, Irish Catholics held only fifteen of the 130 places as magistrates and other petty officials in the city. This “might not concern a day-laborer,” writes Terrence Punch, “but an ambitious Irish storekeeper might resent a system that relegated his race and creed to process-servers and cullers of fish.”

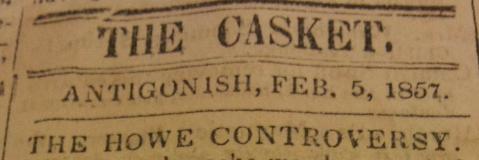

Gradually the reformers entered the House of Assembly. Some of the Halifax-Irish, such as Laurence O’Connor Doyle, served in Catholic constituencies outside of the city (Arichat 1832-1840). Yet, the relationship between the Irish and the reformers was tenuous. Catholics like O’Connor Doyle may have had common cause with Protestants like William Annand on the cause of representative government, but they violently disagreed over Doyle’s advocacy for the repeal of the Act of Union. In 1841 O’Connor Doyle was passed over as a candidate for reform, which precipitated a meeting of the Irish electorate, chaired by Michael Tobin, that resolved to boycott the election. The consequences for reform were ominous as the Tory Andrew Uniacke defeated William Stairs for one of the two seats in Halifax Town. Frustrated, Howe wrote a public letter accusing the Irish of abandoning reform for religion.

[Reformer William Annand (1808-1887) had a productive but tenuous relationship with the Irish Catholics of Halifax]

The precarious coalition between the Irish and reform survived to elect both O’Connor Doyle and Joseph Howe in Halifax County in 1843 and 1847. The realization of responsible government in 1848 was unquestionably a watershed moment for the Irish community as they now had a greater stake in the democratic process. Yet, sectarianism and patronage continued to plague the reform program. In 1854, the former speaker of the assembly (and Michael Tobin’s son-in-law), William Young, became premier. He quickly demonstrated, argued J. Murray Beck, “that he could not manage men.”

Unfortunately for Young, in the same year the Irish Catholic broadsheet, The Halifax Catholic, took an unfavorable view of Britain’s role in the Crimean War. According to Punch, “British reverses seemed to evoke a gloating tendency among the newspaper’s editors.” Eager to recruit fresh replacements for the conflict, the British Parliament passed the British Foreign Enlistment Act in December 1854, permitting the enrolment of foreign regiments, battalions and corps for the British army. The leading reformer, Joseph Howe, traveled to the United States to help recruit one of these “foreign legions.” The men were given cards stamped N.S.R., which on presentation to a customs official could mean either Nova Scotia Railway, or Nova Scotia Regiment. Howe managed to have a contingent of Irishmen sent from Boston to Windsor. When sixty-six men reached Halifax, they were intercepted by the newly elected president of the Charitable Irish Society, William Condon, who persuaded them not to enlist. He also sent telegrams to New York and Boston which read: “Sixty Irishmen entrapped in Boston as railway labourers sent here for the foreign legions.” Howe fled the United States under fear of arrest, and soon after the British ambassador to America, John Crampton, was ejected from the country.

On 26 May 1856, Irish Catholic laborers working on the Windsor railroad line attacked “Gourlay’s Shanty” (a boarding house) and assailed a group of Presbyterians with “pick handles”. It was ostensibly a response to the mocking of Catholic beliefs by a group of Protestants a day earlier. As president of the railway board Joseph Howe was outraged. Shortly after, John Crampton, the disgraced British ambassador, happened to be in Halifax on route to England, and a public meeting was called at Temperance Hall “to consider the propriety of presenting an address to him.” When a group of Irish Catholics publicly voiced opposition, Howe responded with a “merciless tongue-lashing.”

In the Morning Chronicle Howe characterized the entire community as “a band of disloyal Irish Catholics, who undertook to mob people for the expression of their religious convictions.” When the assembly met again in February 1857, the reform government dismissed William Condon from his post at the customs office. Soon after, Catholic reformers slowly began defecting to the James William Johnston Conservatives. Eight Roman Catholic Liberal Assemblymen (and two Protestants representing Catholic districts) ultimately crossed the floor to Johnston (ironically no friend of Catholicism) and the Conservatives.

The defection of the Irish Catholics for the Conservatives was an important moment in Nova Scotia’s political history. It began a brief period of sectarianism that was unlike anything the colony had witnessed to that point. It was disquieting for men like Edward Kenny to read Howe’s repeated attacks on his community, church, and friends. He was simply outraged by Howe’s sentiments that the Irish in Nova Scotia were “eternally tampered with by Irish Priests from Maynooth and elsewhere, who c[a]me out here with their ultramontane notions of religion, and hatred of England, as the staple of their politics, foreign and colonial.” He was even more disheartened to hear that Howe advocated the ill-fated Protestant Alliance to fight “the crimes of the Irish in Nova Scotia.”

The incident also had important repercussions for Nova Scotia’s future. With most of the Irish now in the ranks of the Conservatives, they and their bishop, Thomas Louis Connolly, were overwhelming supporters of the confederation of the Maritime Colonies with the rest of Canada in 1867. The Irish had rallied against the unfounded threat of the Fenian invasions from the United States, and against the notion that they were disloyal. In an 1865 letter to the Morning Chronicle, Bishop Connolly wrote that the Irish in Halifax would “yield to none in loyalty.” His characterization of the Fenians as “knaves and fools” was employed as a means of avoiding the anti-Catholic rhetoric of the 1850s. On 18 September, two days before the federal election, the bishop published an open letter to the Catholic inhabitants of Halifax in which he asked them to support confederation. Catholics in Halifax voted “two for one” for union candidates.

Further Reading:

J. Murray Beck, Joseph Howe: The Briton becomes Canadian, 1848-1873 (Toronto: University of Toronto press, 1984).

J. Murray Beck, “The Party System in Nova Scotia.” The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 20, No. 4 (1954): 514-530.

J. Murray Beck, The Politics of Nova Scotia, Volume One (Tantallon: Four East Publications, 1985).

Shirley B. Elliott, The Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia 1758-1983: a biographical directory (Halifax: Province of Nova Scotia, 1984).

Charles Bruce Fergusson, “Doyle, Laurence O’Connor,” DCB, 9 (1976).

David B. Flemming, “Archbishop Thomas L. Connolly: Godfather of Confederation.” CCHA, Study Sessions, 37 (1970): 67-84.

Philip Girard. “‘I Will Not Pin my Faith to his Sleeve’: Beamish Murdoch, Joseph Howe, and Responsible Government Revisited,” Dalhousie Law Journal, 8 (2001):125-142.

Nicholas Meagher, The Religious Warfare in Nova Scotia, 1855-1860 (Halifax, 1927).

R.J. Morgan, “Kavanagh, Laurence,” DCB, VI (1987).

Terrence Murphy, “The Emergence of Maritime Catholicism, 1781-1830,” Acadiensis, 13, 2 (1984): 29-49. (View Murphy Article)

George Patterson, “The Religious Warfare in Nova Scotia - 1855-60,” in Studies in Nova Scotian History (Halifax: The Imperial Publishing Co., 1940). (View Patterson Article)

Kenneth G. Pryke, Nova Scotia and Confederation 1867-1874 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1979).

Terrence Punch, “Aspects of Irish Halifax at Confederation,” presented at the Conference “Ethnic Identity in Atlantic Canada”, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1981. (View Punch Article)

Terrence Punch, “Joe Howe and the Irish,” Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, 41 (1982): 119-140.

Terrence Punch, Irish Halifax: The Immigrant Generation, 1815-1859 (Halifax: Ethnic Heritage Series, 1981).

Terrence M. Punch, Some Sons of Erin in Nova Scotia (Halifax: Petheric Press, 1980):77-82.

D.J. Rankin, “Laurence Kavanagh,” CCHA Report, 8 (1953): 51-76.