S.S. City of Boston

Holy Cross Cemetery is the final resting place for various men and women that earned their living from the sea. For fishermen, “Jack Tars”, mariners and travellers, the North Atlantic was a perilous force that was both sustaining and threatening. Throughout the Halifax graveyard, the stones communicate the miserable end for many: “Lost at Sea”.

What the faded stones cannot express is the tragic circumstances of those deaths. They cannot adequately express the sorrow of the German immigrant family that lost their three-month-old son, Leopold Edward Rohrer, while crossing the North Atlantic in the winter of 1882.

[grave of Leopold Rohrer]

Often times the markers indicate that multiple family members were lost at Sea. For instance, one stone tells the sad tale of the Deegan family. Captain Patrick Deegan of Halifax was a fairly prosperous ship captain. He had a long career on the sea and spent considerable time in Placentia, Newfoundland, where he met his wife Agnes Roach (a widower). Married in May 1865, they resided first on Upper Water Street and then in a rather large house on Grafton Street. Transporting goods to the United States and Puerto Rico, by the 1880s the family was earning enough to employ a sixteen-year-old servant, Mary Murphy. Tragically, however, in 1890 both Captain Deegan and his son William were drowned aboard their schooner, Laburnum, somewhere off Halifax, while carrying cargo to Puerto Rico.

[Marker of Patrick & William Deegan]

Nearby is the grave marker of Captain James O’Bryan, the skipper of the schooner Ocean Traveller, which was employed in the service of the “Lights and Humane Establishment of Nova Scotia”. After supplying the “lights” along the southern coast of the province, the schooner was set to transport provisions to Sable Island, but returned due to inclement weather. On 18 October 1870 O’Bryan and his crew successfully landed the cattle and supplies on Sable Island and set sail for their return journey to Halifax. The crew was never heard from again and the ship was thought sunk in a heavy gale that occurred the day after the schooner left the island. A few months later, the federal government awarded two months’ pay to the grieving families.

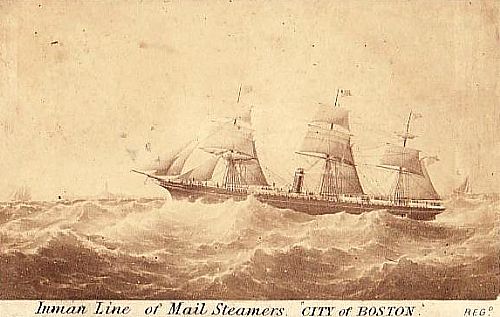

One of the most famous disasters in the nineteenth-century was the loss of the S.S. City of Boston. Constructed in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1864 the City of Boston was the pride of the Inman line. According to the Liverpool Mercury the steamship was “one of the best afloat.” The ship had two engines, four boilers and a number of modern pumps in case the vessel took on water. She also had seven watertight bulkheads, which like the case of the famous Titanic forty-two years later, was supposed to be enough to avoid any engagements with the North Atlantic ice.

In January 1870, having arrived in Halifax from New York (on her forty-third voyage), the vessel boarded passengers and freight (beef, flour, cotton, sewing machines, bacon, wheat, tallow and hops) bound for England. When she steamed past McNabb’s Island, the City of Boston was carrying 191 souls, including military officials and members of some of Halifax’s most prominent families.

When the City of Boston was weeks late reaching Liverpool, England, panic began to spread that it had foundered. There were reports of sightings, and families on both sides of the Atlantic held out hope that the ship would turn up, damaged but afloat. The Acadian Recorder noted that there was much anxiety in Halifax as “a number of [their] most prominent merchants [were] on board...” A Cunard steamer Nemisis, noted upon reaching England that on the night of 31 January they experienced a fearful gale on the banks of Newfoundland, “the worst ever known in that latitude.” “Despite the faint hope expressed by agents of the Inman line” wrote the New York Tribune, “the Steamship City of Boston will never be heard from.”

By the summer of 1870 all hope was lost. In the following months newspapers carried notices that a message in a bottle had been found with news of the doomed ship. In June 1870, the New York Herald noted that a young boy playing on the beach at Staten Island, had found a well corked soda bottle with a message inside indicating that the vessel had caught fire in the engine room and was rapidly sinking. Few gave any of these reports credence and assumed that the City of Boston was either lost in a gale, had struck an iceberg, or had succumbed due to it being overloaded.

One of the more prominent stones in Holy Cross is that erected in the memory of Edward J. Kenny, the son of Sir Edward Kenny, a prominent Irish Catholic businessman. The Kennys were devastated at the loss of their son on the ill-fated City of Boston. One newspaper reported that Sir Edward gave the telegraph office ten dollars for delivering him a message indicating that the City of Boston had arrived in Liverpool. “On hearing that it was a canard,” the paper wrote “he fainted away.” When Lady Kenny died, her obituary noted that she “sustained a heavy blow” from the loss of the vessel from which she never recovered.

[Marker of Edward J. Kenny]

Further Reading: